Review of the Berghain art exhibition

Nothing I had heard about the Berghain art exhibition before going made me want to set a foot in there. The critiques of large scale public funding but low fees for artists together with a pricey ticket left a bad taste in my mouth, but given the opportunity of a free ticket, I tagged along.

The ways the exhibition was riding on the mystique of Berghain-the-club trying to have it carry over to Berghain-the-exhibition-space was also a sore point for me. In the club there’s a no-photo policy with a sticker over your mobile cameras to protect the integrity of queer gender and sexuality expressions and allow people to act and (un)dress freely without the worry of leaving digital traces behind. What does the continuation of that no-photo policy into a socially distanced art exhibition protect? Only an image, the aura of the objects and their associated intellectual property. At least they didn’t keep the notorious security guards at the entrance and pretend to turn people away, but they did search a tote bag we brought – for what? Beer bottles, drugs, another bootlegging recording device, or just a remaining old club security guard reflex?

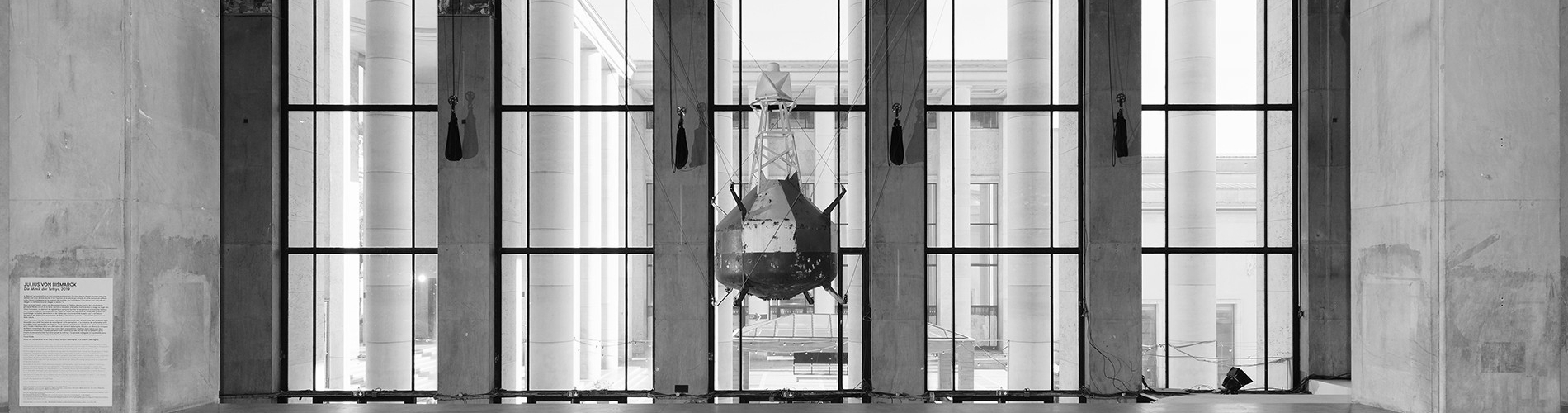

Any doubts I had though were gone already with the first work. Julius von Bismarcks “Die Mimik der Téthys” consists of a massive metal buoy suspended with wires hanging over the first small room by the staircase up to the main dance floor, its weight pressing down on you and casting its shadows over the room as it is slowly being pulled by weights in black bags at the end of a pulley system making it seem like its floating on water. The work is originally meant to highlight the kinetic force of nature as it is connected with a sensor to an actual buoy in an ocean somewhere and mimics its motions. But in this space, it is also bringing back memories of the machinic aliveness that used to inhabit this building and why not the floating movements of a crowded dance floor.

As impressive as the first work was, the exhibition seen in the main dance floor after ascending the stairs can be nothing but a disappointment. The silence as a painful reminder makes it impossible to shake the memories of nights spent here and no art work can compete with the symbolic weight of the empty metal DJ booth at the back of the room and the silence of the hibernating “Function One” sound system.

Still some works manage to blend with the space. Mechanical works and large sculptural works with harsh materials works best, naturally. There’s a gothic fountain on a metal bed with a floating candle. In one room, a mechanical piano plays single, echoing notes. I cant give more details than this, not even the artist names, because I have to write this review from memory.

Throughout the exhibition you are led through a strict path through familiar and unfamiliar rooms of Berghain with signs over entrances pointing out that if you cross this doorway there is no turning back, complete with staff sharply telling you off if you try to go the wrong direction – the only expression of human contact left in this post-hedonistic space.

The exhibition is huge and seemingly never ending. Every time you think you reached the exit, a new room emerges – including the incredible spacious, raw and (at least for me) unexplored and undeveloped second half of the Berghain building. Again, massive sculptures mimicking the tough materials of the building itself as well as its past visitors and their garments stand out as well as a number of works of almost mythological stature featuring ravens, hieroglyphs and human statues. Surprisingly also a few works projecting natural soft objects like forests and wood stand out as contrast.

The final room – Säule – divided only by a thin enclosure of glass and black metal from the first is again dedicated to an individual work. This time the in-house artist Wolfgang Tillmans and his music video for “Life Guarding” projected in portrait mode on one of the walls. An existential swan song (the video again referencing a dark ocean) bringing home the feeling that this exhibition is as much a funeral of what is no longer there, of a dying culture, as an exhibition in its own right, but a worthy one at that, I have to say – it was very hard to leave that last room.

Berghain can never be an exhibition space standing on its own merits. This is the first and only exhibition of the kind that is possible here, forced through with desperation, state support and small artist fees with the former hedonism as a constant backdrop wherever one looks and listens.

What the future hold for Berghain and the Berlin club culture, no one knows. It goes far beyond predictions of the developments of vaccines or rapid testing for Covid-19. You leave this exhibition with feeling that something irrevocable is already lost and when you look back, all you see is an angry German security guard telling you: NEIN!