Hot Line Riot 17 September 1982

Republished from Cybernorms but their site is down for the moment.

This text is yet another version based on my research into the Hot Line riot of 17th of September 1982. Earlier versions consists of an article in Arbetaren Kultur and a presentation at Make All at the Technical Museum in Stockholm on the 18th of August.

The research is to a large extent based on an analysis on newspapers on microfilm from those days. Those who want to read the scanned newspapers I refer to can do so here. I also want to thank Kugg and Linus for helping out with the reserch.

Sequence of Events

It was not the first time that the youths had decided over the hot line to meet at Fridhemsplan [a major central intersection and metro station]. This is how it sounded in an article in Aftonbladet the 9th of September.

The new amusement for young people in Stockholm is impromtu group conversation by phone.

You dial a number without subscriber. Between the beeps of Televerket (the state telecommuncations authority and public telecoms company) and the automatic voice “please dial…” up to 15 people can simultaneously talk and shout to each other.

Here’s how it sounded at 8:30 in the morning on number 08 13 00 20:Beep beep beep beeeeep… Please dial 90 120 for information…

(A murmur of voices, hello, hello, is Goran there?)

(Girls voice:) Is there any boy on the line?

(Boy:) Yes, me!

Are you the one they call “Klark Gabble”

Sure

Oh, is there no one else?

I’m also called Clark Gable…

(Other boys voice:) Goran!

Oh knock it off, ther is no Goran

(Girl:) So where are you from?

(Clark Gable:) Enköping.

Are you going to Fridhemsplan tonight?

Well, I don’t know.

(Beep beep beep beeeeep… Please dial…)

But already a few weeks later the number of youths had exploded. Social networks and rumors, like viruses, spread exponentially. One tells another. They tell two more. The four become 8, then 16, 32, 64 and so on and so forth. Not only that. Along the way they may also encounter a true hub, an extremely well-connected supernode. That’s when the spreading completely explodes. Such a thing must have happened between the 9th of September and the 17th of September that we now move to.

A beutiful autumn evening in September 1982 a few dozen motley attired young people gathered at Fridhemsplan: ordinary schoolchildren, no organized motorcycle gangs. Neither the city’s few punks and anarchists were represented except by a few delegates. Continously new youths arrive from the depth of the underground metro station. No one knew where they came from and what their intentions were. The didn’t seemed to demonstrate for or against anything. They just stood there in loosely connected groups, talking to each other.

Their numbers soon reached a thousand people. Nothing like this had ever been seen: uncontrollable, yet so calm. Perhaps they had a secret plan? Maybe they were under the influence of something? Maybe they were looking for trouble? The police though it was better to be safe than sorry and decided to disperse the crowd.

They were everywhere, says Commissioner Kjell Andersson. On the roof of the bus shelter and the election booths, in the trees and the power lines. But they scattered when we arrived. (EX820918)

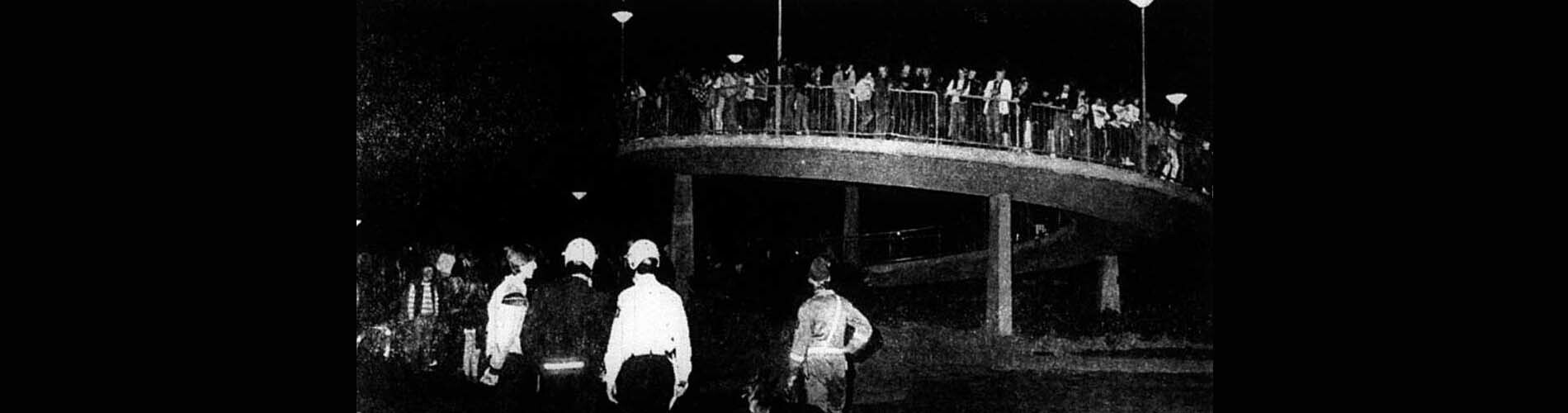

Instead, the crowd move to the nearby Rålambshovs park without marching order, without slogans, without predetermined plan. The youths gather on top of the footbridge at the park, the police close behind. A tense situation arise. Someone throws a bottle. That triggers the police to enter.

Fifty police officers with riot gear and dogs move in to in to disperse the crowd. The youths start to throw rocks, beer cans and bottles from the footbridge. Commissioner Kjell Andersson later describes it as if “it was some sort of mass psychosis. More and more people started throwing things”. (EX820918)

People were hit by batons, bruising occured. Some claimed they had been bitten by dogs. Four policemen were injured by flying objects. Ten youths were taken into custody and had to be picked up by their parents. By 22 o’clock, the youths had dispersed and everything went back to normal.

Reactions the Following Day

The day after this headline shows up in Aftonbladet: “Hot Line fans fight with police” (Soccer hooligans was probably the only street violance that they were aware about…).

The teenagers, most of them between 14-18 years of age, didn’t know each other […] They had come into contact through the “hot line” – the new craze that through the misstake of Televerket allows an unlimited number of people to be connected to the same telephone line.

(AB820918)

The rumor goes that Televerket are going to shut down the hot line. “We sign protest lists against Televerket. Where should you now be able to get into contact with each other? says Sanna Norelid, 16, from Djursholm [a rich suburb] and she was eagerly supported by her unknown comrades who fought they way forward to sign the lists.” (AB820918)

Indeed, commissioner Kjell Andersson fears new riots. “Now we fear what will happen tonight, says Kjell Andersson. If there are new riots with stones-throwing we have to ensure that Televerket stops the “hot line” immediately”. (EX820918)

Svenska dagbladet notes that this was not the only event of its kind with a short notice the day after:

Several large gangs roamed around Stockholm on Friday evening and caused the police great concerns. Several youths were arrested, including in the Rålambshovs park where they indulged in throwing rocks on the police. At the Norrmalm police the detention was almost packed already at 22 in the evening. Large gangs also ravaged in Gärdet, on Lidingö, on Ekerö and on Bromstensfältet. (SVD820918).

Also Expressen acknowledges that it was a messy weekend. Youths have been seen “flipping over cars, breaking windows and burning election posters in Stockholm City”. At a rock concert in Sergels Torg (the central square) the youths gathered posters and set them on fire. When the police came to arrest them their friends attacked and tried to free them (EX820920). The youths acted as if possessed by something…

After the initital reactions the news about the incident drown in two major events. On Sunday, the headlines are covered by the massacres in Sabra and Shantila in Lebanon that cost almost 1000 lives. On Monday, the news flow is dominated by the electoral victory of Olof Palme that marks the end of the Social Democrats six years as an opposition party.

The Establishment of an Official Line

However, a small notice on the front page of DN on Sunday says: “Slutringt på heta linjen” (No more calls on the hot line). Further into the paper we learn that Televerket has called in twenty experts that are going to shut down the numbers used for the hot line. The extra personell follows directly on a visit from the police that demanded an end to the calls.

The telecoms authority explain how the hot line works:

“The hot line” is actually many lines. It is subscriptions that has ended but where ther is a reference tone and the message; please dial 90 120 for information.

- Televerket has be generous and let the reference remain several years after the subscription moved or cancelled, says Bengt Källsson.

All lines that are not used are connected to a special equipment where the lines are put in parallell and an answering machine has been plugged in. When several people call a number that has ceased they can speak or shout [sic!] to each other.

(DN820919)

DN explains further how the youths came across the numbers:

The current phone numbers are spread with lightning speed. Often the youths share the phone numbers when they talk on the hot line. An 18-year-old boy told DN on Friday evening that he had a list of 60 numbers that went to hot lines.

(DN820919)

There’s our supernode…

However, Televerket are not so heartless that they just shut down the lines. They understand after all that there is a social need, particularly for “old, sick and disabled”. Instead they will explore the possibilities of organizing “serious group calls”. (DN820919).

An official number is eventually established, but under different house rules. Only 5 people are allowed to talk simultaneously and then only 5 minutes at a time. Presumable the police also have a ear on the wire on Friday evenings. In this way, a social need can be fulfilled without for that matter having unforseen events occuring in the city on the weekends.

The official line later turn into private hot lines that still today can be sighted in small newspapers ads. The private lines hasn’t caused much fuss, although many certainly have fond childhood memories of them. The only controversy that arose in recent years was a murder in Malmö in the 90’s where two men had decided to meet over the hot line and one killed the other. But this time, no one got the idea to blame the medium. Instead, the individuals psychologic orientation and homophobic motives were seen as the cause.

The Great Compromise

The quotes in the beginning of this text are from Hans-Magnus Enzensbergers “Swedish Autumn”, one of the few longer accounts of the events and taken from the philosophers book “Europe, Europe” where he travels around seven European countries and captures the zeitgeist. The hot line riot and its consequences is looked upon by him as a sign of a typical Swedish relationship to the state and trust in social institutions.

He is amazed by the discovery of a new mass medium, what he considers to be a “social innovation of the first order”.

It’s hardy possible to use modern communication technology more intelligently. I don’t know if the city of Stockholms awards a cultural prize. If it does, then the unknown discoverers of the “hot line” have done more to deserve it than all the aspiring performance artists in the kingdom. That should be clear even to the higly paid experts whom for decades have bored audiences with their troubled statements on the aimlessness, weak motivation and anomie of current youth.

The reaction from society was as we know not a prize, but an attack by the police. Enzensberger as German is of course no stranger to violent police action, but still says:

In the Rålambshovs park there was no illegal squatting; there were no masked faces or molotov cocktails, just a few hundred young people who wanted to talk to each other.

Their crime was simply that they had not called upon any of the resposible institutions available for this purpose. If they had applied to the appropriate office with a request to organize a meeting place for aimless, weakly motivated, anomic young people, they would have been met with sibsidies instead of police truncheons. Crowds of social workers, youth counselors and community art workers would have descended on them to help them achieve socially desirable forms of communication.

And indeed, the institutionalization of the hot line arrives, where both Televerket and the police are pulling the strings. A delegation of youths from the hot line meet Televerket and arrive satisfied with the insurance that the youths will get their own “hot line” from the telecoms authority. Enzensberger:

The logic of state intervention is quite clear: first the stick, then the carrot. The social imagination and independent initiative of the young people are crushed in a kind of pinchers movement – repression on the one hand and the state’s embrace on the other.

And from that moment on the police dogs can remain in their kennel. The sheep that has found its way back into the fold encounters only helpfulness and understanding.

According to Enzensberger the Swedes think of their institutions as an alien but benevolent power. Clearly, it was unfortunate this thing with the police dogs and the batons, but they just didn’t understand. As soon as the youth delegation had explained they realized that there was a legitimate social need. In this way a “moral immunity” emerges around the institutions where only one with “evil intent” would get the idea to resist their power. Once inside the institutions there is only warmth and helpfulness, life is simple and everything works. Out in the cold you not only risk harm but also that any fun you’re up to can be shut down.

The Power of Media

Enzensbergers sociological analysis in all glory, but the most interesting theory was still the one developed by the Swedish police. There, all so-called social explanations are completely absent. Here the blame is not put on lack of youth centers, the dismantling of the wellfare state or the individualistic culture of capitalism. No inherent logic in Swedish society has contributed to these stray youth gangs. To the Swedish police there were no doubt that the hot line had caused the riot. Not only that, the police believe that the bug in the phone system also explains why in recent times “very large young gangs have emerged in Stockholm” that often has led to vandalism and fights with the police (SVD820920). If only the hot line, this mass psychosic inducing medium, is shut down, the youths will most likely calm down. Not since the German media theorist Friedrich Kittler claimed that the “so-called man” is only a function of the contemporary technical mediastandards has anyone taken the power of media so seriously.

Similar conclusions is also drawn in similar debates arising in the 80’s. Kung-fu flicks cause the riots in Kungsträdgården and W.A.S.P causes satanist suicide cults. And of course the Rave Commission and their fight against repetetive hypnotic rythms the following decade.

However, I don’t want to dismiss these moral panics to easily. That would be to deny the transformative effect of new media. Sure, everything calms down after a while when society have gotten used to them, but that is only the dust settling after a great battle where social dynamics and power structures have already been altered. How many wouldn’t, like me, have had very different lives if not the internet got in the way sometime during adolescence and opened up whole new worlds? It was almost like a mass psychosis but in a positive sense. The hot line is also an espacially interesting case since it redrew the social networks within a limited urban area. The hot line forms a social sphere that cuts right across schools, regions, classes and center-perifery relations that otherwise divide social groups from each other.

A World on Their own

What the hot line, the riots in Kungsträdgården (when there still wasn’t any surveillence cameras in the city) and at least the early internet have in common is that they all create a social sphere where mostly young people create communities with their own norms and social behaviors, without transparency for either regulatory institutions or social workers – a social sphere that gives the possibility to restart a whole new life instead of the one handed down through social heritage.

Long before Facebook and Gooogle gave direct access to their users personal data to intelligence agencies and long before FRA plugged in their cables and copied all Swedish internet traffic to their databases, the internet was also that kind of social space. Before web pages and even internet service providers existed anyone with a phone modem and a computer could call up another computer and exchange information. Thanks to clever phone hacks that made international long distance calls completely free this developed into a global social network long before Carl Bildt in 1994 sent the first email between heads of state to Bill Clinton.

For Kittler it is our media that determine the boundaries of what we can experience and imagine. But this has nothing to do with the content of the media, which he just as McLuhan more or less ignores. It is not the content of novels, movies or philosophical manifestos that exhibit new worlds that inspire to action. For him, it is instead the technical structure of the media that set the boundaries – which connections and messages it allows or filters away, who can transmit, receive or overhear. New media creates new possibilities of communication and social groupings that draw new borders between participant and outsider.

Comparisson with Net Politics

Apart from Enzensberger account, references to the event is scarce, despite it having such a unique character. The only mention I find online is the blog Mothugg that read Enzensbergers text in 2011 and correctly pointed out that the story of the hot line riot is very reminiscent of todays discussions about net politics – “long before terms such as flash mobs, phreaking, hacktivism, social media, or for that matter, net politics became public property of the Swedish language”. Also the tactic of taking something free, shutting it down and making an official version of it has recently been termed “spotification”.

A contemporary news item about the incident might have been as follows:

Net politics: A flashmob that occured through social media ended up in a confrontation with the police on Friday evening. The police suspects that a group of phreakers are behind the hacker attack against the telephone system that enabled the anonymous metting place where the event was created. The police fear that there is a risk that the anonymous network can be used for organized crime and therefor intends to shut it down.

On Monday the 17th of September it is 30 years since the hot line riots. That means we have but a few weeks left to plan how to best celebrate the anniversary. Are you going to Fridhemsplan tonight?